Japanese shore juniper (Juniperus conferta Parl.)

found naturalized in southeastern Massachusetts

Introduction

The recent general decline of the native common juniper

(Juniperus communis var.

depressa Pursh), which we have been observing in

eastern Massachusetts, can be readily explained by the plant's light requirements.

A rapid process of reforestation of post-agricultural and other man-made

forest openings has resulted in decline of many sun-loving native species

including junipers. Fertile, healthy common-juniper clones in eastern

Massachusetts have become exceedingly rare. One patch of common juniper

growing along Ponkapoag Trail in the Blue Hills Reservation has literally

disappeared within five-six

years in front of our eyes. That's why our attention was attracted to a

large, healthy, fertile population of a prostrate juniper on slopes of a

road/ramp crossing a highway and aggressively spreading down into sparse

pine forest.

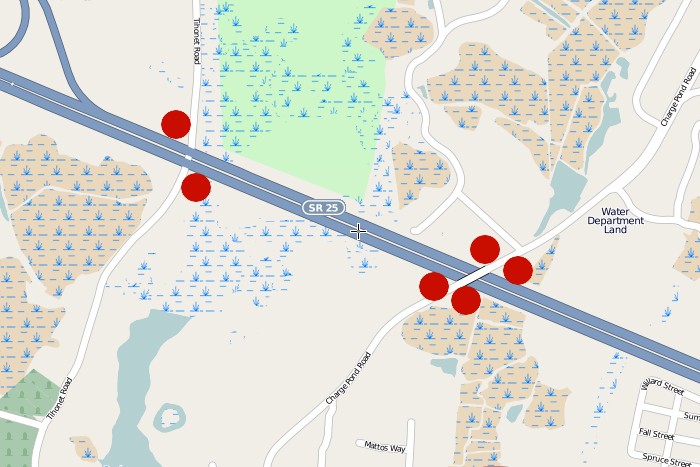

The juniper covers man-made slopes of a ramp in Wareham,

MA, where Charge Pond Road crosses a state highway, Rt. 25. Wareham is a

Greater Boston's South Shore community and a gateway to Cape Cod: Rt. 25

is leading to Bourne Bridge built across the Cape Cod Canal. Present on

both eastern and western slope of the ramp crossing

Rt. 25 and on both northern and southern side of the highway, the

population is covering an estimated total area of about 0.5 acres (2,000

sq. m), producing abundant cones in its most lighted

parts.

A closer examination of samples has shown that the plant, even

though much resembling the native common juniper, appears to be Japanese

shore juniper, J. conferta Parl.

Introduced to the US less than a hundred years ago, in 1915 (Rehder

1940), shore juniper is now widely cultivated in North America, available

at many nurseries. This vigorous prostrate salt-resistant

shrub is recommended by the US Department of

Agriculture and Massachusetts

Office of Coastal Zone Management for slope, beach, and dune

stabilization. As far as we know, no cases of naturalization have been

reported. This species is not on the Massachusetts Checklist (Sorrie and

Somers 1999), not even in the Flora of North America (Watson

1993 in FNA, Vol. 2).

Morphological Characters

J.

conferta superficially resembles the native J. communis

var. depressa. Both belong to sect.

Oxycedrus, whose members have only acicular (prickly,

needle-like) leaves and no scale leaves. The leaves are jointed at base,

with a single white band of stomata on the upper (adaxial) side. (The

latter character is observed more consistently on live plants or fresh

samples. In old herbarium samples white bands may be less pronounced or

altogether disappear.)

Another native juniper, J. virginiana L., while

belonging to a different section (Sabina), in its

juvenile form, when lacking mature scale leaves, may also be confused with

common juniper. However, in all representatives of the section

Sabina including J. virginiana,

the juvenile (prickly) leaves are decurrent, that is, running

down onto the branchlet, while in the section

Oxycedrus leaves are jointed at base, not

decurrent.

Therefore, in Massachusetts the real challenge is to differentiate

only between the alien J. conferta and closely

related native J. communis var.

depressa. A comparison of morphological descriptions

yielded the following differences.

- Leaf and cone size. While in J. communis var. depressa leaves are 0.8-1.8 cm long and cones are only 0.6-1.0 cm in diameter (Fernald 1950), in J. conferta, both leaves and cones are larger: leaves are 1.5-2.5 cm long (Voroshilov 1982), cones to 1.2 cm in diameter (Rehder 1940, Voroshilov 1982).

- Leaf cross-section. While in J. communis var. depressa leaves are only slightly concave above and bluntly keeled underneath, in J. conferta they are deeply grooved above (becoming folded on drying), their keels more pronounced below.

- Habit. In the Japanese species, leaves are very crowded, the whole plant thus looking more vigorous, yet at the same time more prostrate and compact, forming denser mats (indeed conferta means 'dense'). While the native prostrate form of common juniper may have branches ascending as high as 1.5 m (Fernald 1950), Japanese shore juniper is strictly procumbent (Rehder 1940), in this respect resembling J. horizontalis Moench. more than any other eastern North American juniper.

The enormous range of J. communis has

apparently resulted in development of geographical varieties within the

species, var. depressa being only one of a few. Among

known varieties of common juniper, there is a northern (Canadian) var.

megistocarpa Fernald et H. St. John characterized by

abundant, large cones and very depressed, trailing clones. However, in all

its prostrate varieties including var. megistocarpa,

J. communis appears to retain relatively short

leaves—shorter than leaves in its upright forms, much shorter than in

J. conferta, and not as dramatically concave.

Discussion

Sad experience with many introduced plants is to result in much more

cautious approach to new introductions. The least vigilance has been

applied to alien gymnosperms (conifers), which are less known as invasive plants,

as compared to angiosperms. A latent period has been typical for all newly

introduced plants that later became invasive, though its duration was

different for different species. It definitely takes a conifer a longer

time to develop a vigor in a new setting enough for it to become

invasive.

One interesting example of an aggressive alien conifer is Norway

spruce (Picea abies Karst.), whose year of

introduction to the US is unknown because it happened so early. This is

one of those few conifers that has had enough time on the North American

continent to develop a few generations and attain a menacing vigor; yet

Norway spruce is not currently recognized as a threat in many states

including Massachusetts. Here it is still playing an important role in

plantings, even within reservations. The reason might be that, once it is

planted, Norway spruce has to go through a prolonged latent period, during

which it appears harmless. From now on, Norway spruce expansion in Massachusetts parks may

speed up significantly due to presence of new generations of fertile

trees.

The population of Japanese shore juniper in Wareham may also

eventually expand faster, especially if there are viable seed in

existence. It most probably is originating from a few shrubs planted along

the newly constructed road/ramp less than 25 years ago, in 1987. Over the

years the juniper has descended to the pitch pine forest at a lower

elevation, away from the road. It appears to be spreading

vegetatively—despite the presence of abundant cones—or at least we cannot

report any findings of seedlings. Separate small patches appeared to be

connected with other parts of the population under the forest litter. A

similar spreading planting of

J. conferta

(planted together with J. horizontalis)

is found at the next bridge across the same

highway, about 2 miles west.

Alarmed upon finding a thriving population of an exotic juniper in

eastern Massachusetts, we have been revisiting other juniper locations

known to us. None of those re-examined so far have proved to be

non-native. However, we have to look out for more populations of Japanese

shore juniper, especially in the coastal situations in Plymouth and

Barnstable counties. In the case of the successful Wareham population, we

may be dealing with an early manifestation of a future problem.

References

Fernald M. F. 1950. Gray's Manual of

Botany. 8th ed. American Book Company. 1632 pp.

Rehder A. 1940. Manual of Cultivated Trees and

Shrubs Hardy in North America. 2nd ed. The MacMillan Company.

996 pp.

Sorrie B. A. and P. Somers. 1999. The Vascular

Plants of Massachusetts: A County Checklist. Massachusetts

Division of Fisheries and Wildlife. Natural Heritage and Endangered

Species Program. 187 pp.

Voroshilov V. N. 1982. [Guide to the Plants of

the Soviet Far East]. Nauka Publishers. 672 pp. (In

Russian)

Watson F. D. 1993.

Juniperus.

In: Flora of North America Editorial Committee,

eds. 1993+. Flora of North America North of Mexico. 12+ vols.

New York and Oxford. Vol. 2, pp. 412-420.

Irina Kadis & Alexey Zinovjev

31 March 2011 - 23 May 2011