Examples of close Euro-American connections:

Two Mediterranean species of Salix

A. K. Skvortsov

Euro-amerikanische verwandtschaftliche Beziehungen

zweier mediterraner Salix-Arten

Feddes Repertorium 1971, 82

(6): 407-420. Berlin

Translated from German by Irina Kadis

Translator's Note:

This article was written 36 years ago. We are providing the entire text, the way it

was published in German, except for the lists of herbarium specimens. According to the author himself,

this treatment is now partially outdated--particularly as regards the Californian willows.

However, the author has not changed his opinion regarding

S. tristis

and

S. humilis.

According to the contemporary treatment by G. Argus (1997), the American species mentioned in this

article are placed as follows:

S. lasiolepis and

S. irrorata to sect.

Mexicanae;

S. lemmonii and

S. geyeriana to sect.

Geyerianae.

As for

S. hookeriana, G. Argus has placed it together with

S. humilis var.

humilis and

S. humilis var.

tristis

in sect.

Cinerella, which corresponds to

sect.

Vetrix subsect.

Laeves in Skvortsov (1968).

This section as well includes the European species:

S. aurita,

S. caprea,

S cinerea.

The translator is grateful to Anett Hofmann

(University of Zurich)

for advice on some difficulties with German.

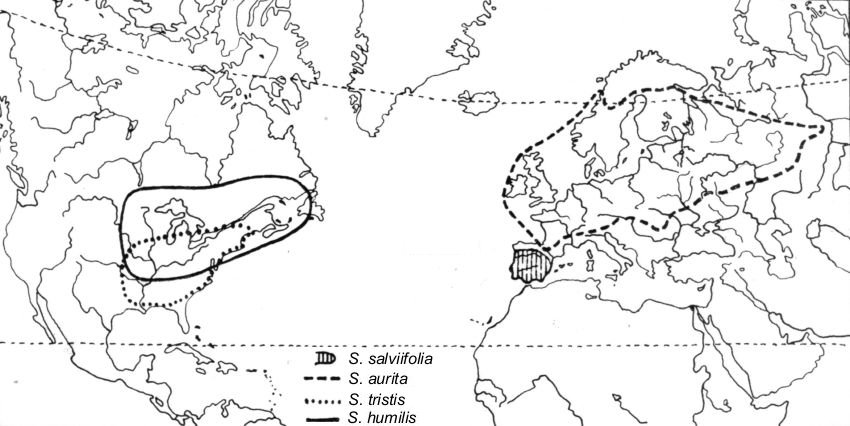

Abstract

The author shows a close relationship between

Salix salviifolia Brotero, a species distributed

across the Iberian Peninsula, and the eastern North American

S. tristis Ait. Both species, along with the

European

S. aurita L. and American

S. humilis Marsh., form a group of

closely related species within the subsect.

Laeves, sect.

Vetrix.

Salix pedicellata Desf., a

species with broad Mediterranean distribution, is related to the western

North American (mostly Californian)

S. lasiolepis Benth. The latter relationship, though it appears to

be more distanced than the former, is also apparent.

S. lasiolepis along with the closely related

S. hookeriana Barr. present a western

North American counterpart of the Old-World group of

S. pedicellata within the subsect.

Vulpinae. The available botanical evidence

supports the hypothesis of direct trans-Atlantic origin of these

connections rather than the explanation employing complicated migratory

processes across Beringia and East Asia.

Introduction

The phylogenetic relationships between willows of the Old and New

World so far rarely have been a subject of discussion. The only study was

undertaken in the 19th century by the renowned

Salix researcher N. J. Andersson (1858, 1868).

Andersson's conclusion was that "of 58 North American species, 24 are

identical with European ones; 24 belong to the same types, and only 10,

either western or Arctic forms, seem to be peculiar to this great

continent." (Andersson 1858). Though this researcher succeeded in pointing

out a number of valid connections, this conclusion of his today presents

only historic interest. The number of willow species known from North

America has grown more than twofold. Besides, the number of species common

with Europe is only half as large. If we take into account the five

European species that are widely cultivated in North America and

naturalized, then the total number of common species is still only 12.

From the perspective of contemporary knowledge, the majority of

Andersson's conclusions as regards species relationships appear incorrect.

(For example, he related

S. coulteri

and

S. lasiolepis to the European

S. daphnoides;

S. barklayi to

S. glauca;

S. phlebophylla to

S. retusa; he also considered

S. lucida to be a subspecies of

S. pentandra, etc.)

The relationships of the Old- and New-World willows have never been

revised since Andersson's time. Taxonomic research on the American and

European willows went on along two completely separate paths, totally

independently. C. K. Schneider (1920a, b) was studying Eurasian willows,

while his monographic description of the American species was not

completed. Most importantly, Schneider followed the American tradition in

his revision of the American willows and never succeeded to compare the

sections delimited within the New World with those described in the Old

World.

At present we have sufficient information only on the latest

(apparently Quaternary) Eurasiatic-American relationships within the genus

Salix. They are manifested first and

foremost among Arctic, Arctic-Alpine, and sub-Arctic species that are

common for both hemispheres (

Salix reticulata L.,

S. vestita

Pursh,

S. herbacea L.,

S. polaris Wahlenb.,

S. phlebophylla Anderss.,

S. rotundifolia Trautv.,

S. glauca L.,

S. ovalifolia

Trautv.,

S. arctica Pall.,

S. chamissonis Anderss.,

S. fuscescens Anderss.,

S. lanata L.,

S. alaxensis Coville,

S. pulchra Cham.,

S. sphenophylla A. Skv.

[1]

Specimens of the latter species from Alaska were identified by Hulten (1968) as

S. arctica

ssp.

torulosa

.

) and also in the boreal

S. bebbiana Sarg. Close affinity of the boreal American species

S. serissima Fern.,

S. planifolia Pursh, and

S. pedicellaris Pursh with the Eurasian

S. pentandra L.,

S. phylicifolia L., and

S. myrtilloides L. has been long known. The

author has highlighted (Skvortsov 1966) close connections between the

Siberian

S. boganidensis Trautv. and

S. erythrocarpa Kom. on one side and

the American

S. arbusculoides Anderss.

and

S. nivalis Hook. on the other

side. Hulten (1968) has noticed the presence of

S. hastata, an Old-World species, in Alaska.

These examples repeatedly refer to just Arctic and Arctic-Alpine species.

For the majority of American willows, the Old-World relations remain

unknown. Clarification of these connections presents the most important

and challenging goal of the

Salix

research.

This work is an attempt to approach the task through clarifying

relationships of two European willows,

Salix pedicellata Desf. and

S. salviifolia Brot., with American species. These links might

present interest not just for the willow research, but also to some extent

for the study of the Mediterranean flora and its connections.

Studied material and acknowledgements

This work is largely based on the study at the Herbarium of the

Botanic Institute in Leningrad (Curator Prof. I.T.Vassilczenko). Prof.

G.Moggi has kindly made it possible for me to handle extensive material

from the Herbarium of Florence University. Rich and valuable collections

of

S. salviifolia were received as

exchange from Dr. A.R.Pinto da Silva (Oeiras, Portugal). Some American

samples were provided by Prof. C.L.Hitchcook, Dr. Th.Crovello, and Dr.

P.H.Raven from the United States. A number of samples were studied by the

author in the Botanical Museum in Copenhagen (Director Dr. A.Skovsted).

Many thanks to all the colleagues.

Relations of Salix salviifolia

Brot.

The geographic area of this species is entirely within the

Mediterranean Floristic Area, provided that the Area is delimited in the

modern sense (see Meusel, Jäger, Weinert 1965). Yet

S. salviifolia is not purely Mediterranean or

sub-Mediterranean; even more appropriately it might be called

Mediterranean-Atlantic. This is true not only because it is distributed on

the Atlantic Coast, but also since it is more abundant in the western

areas of the Iberian Peninsula, in Portugal, than in the inner parts or

Mediterranean-Sea-facing areas of the peninsula.

S. salviifolia has not been found anywhere

outside the Iberian Peninsula.

The dense white-wooly tomentum of the lower leaf side is

characteristic for

S. salviifolia.

Indeed the species received its name because of this tomentum. This kind

of tomentum is found in species of sect.

Villosae (

S. lapponum L.,

S. alaxensis

Coville,

S. helvetica Vill.,

S. kryloviiE. Wolf,

S. candida Willd.) as

well as in sect.

Canae (

S. elaeagnos Scop.) Due to this similarity, some

authors (Andersson 1868, Pereira Coutinho 1899) were inclined to place

S. salviifolia close to the named

sections. Yet in the rest of its characters

S. salviifolia is rather different from the species of these

sections. It should without doubt be assigned to sect.

Vetrix (Vicioso 1951, Skvortsov 1968). More than

that, sections

Canae and

Villosae belong to a phylogenetic line that is

entirely different from that of sect.

Vetrix. The white villous trichomes of

S. salviifolia constitute one of many examples

of parallelism and convergence, which is so widespread in the genus

Salix (Skvortsov 1968). In other

species of sect.

Vetrix (such as, for

example,

S. pedicellata Desf. or

S. kuznetzowii Goerz), one can also

find specimens with nearly just as white and dense hairs.

Among Eurasian willow species, it is

S. aurita L. that is the closest to

S. salviifolia. From the first glance the two species look rather

unlike each other: one of them has narrow leaves covered with dense white

hairs, the other has broad leaves with sparse gray hairs. However, a

thorough morphological study of their organs reveals much

similarity.

One more species that has a lot in common with

S. salviifolia is the American

S. tristis Ait. Since Andersson's time (1859,

1868), most authors (including Schneider 1920a) mistakenly united this

willow with

S. sericea Marsh. and

S. petiolaris Sm. However, Ball (1947)

correctly placed

S. tristis in sect.

Vetrix (

Capreae). The position of this species can be

pinpointed even further. Together with

S. aurita and

S. salviifolia,

S. tristis forms a natural, wholesome

entity within subsect.

Laeves of sect.

Vetrix. As compared to the rest of

Vetrix representatives (such as

S. caprea L. or

S. cinerea L.), the members of this group

possess the following characters:

- shoots rather slender and short, more or less

covered with gray tomentum

- wood surface striated

- leaf petioles short; leaves mostly small, their

broadest part above the middle, revolute at margin, with rugose upper

surface, pronounced veins surfacing on underside, and more or less

tomentose pubescence

- flowering buds small, deltoid-ovoid

- catkins small, fruiting ones rather slender when

expanding, short in maturity; male catkins not larger than 25 x 16 mm

in S. aurita; in S. salviifolia and S. tristis even smaller than that (whereas

catkins of, say, S. caprea often

become as large as 50 x 27 mm)

- bracts small, mostly obtuse and only seldom entirely

black; they are mostly colored purple-brown or entirely pale, with

scarcely blackish tips

- anthers small when dry: 0.5-0.6 mm long, as compared to 0.7-1.1 mm in

S. caprea-S. cinerea group)

- styles and stigmas rather short (stigmas about

0.2-0.4 mm long)

- S. aurita and

S. tristis are known to be

restricted mostly to poor, acid soil; we don't know for sure if this

is true for S. salviifolia;

however, it is quite probable.

It is not easy to decide to which of the two related species

S. salviifolia is closer. Its

pronounced wood striation, the shape of buds and stipules, as well as male

catkin morphology make it closely resemble

S. aurita. In its leaf shape and pubescence as well as in

morphology of developing fruiting catkins,

S. salviifolia has much in common with

S. tristis. As regards other characters, such as petiole length,

leaf blade size, degree of stipule development, or catkin size,

S. salviifolia occupies a position intermediate between

S. aurita and

S. tristis. In comparison with the other two species' characters,

those of

S. salviifolia can be

presented as follows:

|

S. salviifolia

|

S. aurita and

S. tristis

|

|

A tall shrub or a small tree. Pubescence on leaf

undersides very much pronounced, mostly white.

|

Mostly tall or small shrubs. Pubescence on leaf

undersides mostly gray, often disappearing in mature leaves.

|

|

S. salviifolia

|

S. aurita

|

|

Leaves 4 to 7 times as long as broad.

|

Leaves 1.5 to 3 times as long as broad.

|

|

Leaf margin mostly denticulate or entire.

|

Leaf margin mostly irregular, undulate, coarsely dentate.

|

|

Leaf

apex acute or more or less obtuse, straight.

|

Leaf apex rounded

or abruptly attenuating in a short, often crooked

point.

|

|

S. salviifolia

|

S. tristis

|

|

Wood striae mostly pronounced, long, multiple.

|

Wood striae small, sparse.

|

|

Stipules broad, inequilateral, obtuse.

|

Stipules

smaller, often nearly lanceolate and nearly equilateral,

acute.

|

|

Floriferous buds broad deltoid-ovoid.

|

Floriferous buds narrower: up to

oblong-ovoid.

|

|

Male

catkins oblong-cylindric, 15-25 x 10-14 mm.

|

Male catkins oblong to nearly globose,

6-12 x 7-10 mm.

|

S. tristis is distributed in the

eastern US from Massachusetts to northern Florida, westward to North

Dakota and Nebraska.

In American literature

S. humilis Marsh. is commonly positioned close to

S. tristis. According to such researchers as

Griggs (1905), Schneider (1920a), Argus (1964),

S. humilis and

S. tristis are just two extremes connected through a number of

intermediate forms. This concept might be not right. Morphologic

boundaries between species and diagnostic characters definitely require

further elaboration, yet the treatment of

S. tristis as a distinct species already appears to be sufficient.

S. tristis differs from

S. humilis morphologically, ecologically, and

also geographically.

S. humilis may be

considered as yet another, fourth member of our species group. The

majority of diagnostic characters for this group that have been described

here above also fit

S. humilis. At the

same time,

S. humilis, due to some of

its characters, constitutes the link connecting the group of

S. aurita-

S. salviifolia-

S. tristis with

S. caprea.

Leaves of

S. humilis, glabrous

on the upper side, covered with spreading trichomes on the lower side,

with their relatively long (4-12 mm) petioles, resemble

S. caprea leaves.

Some samples of

S. humilis with

leafy branches generally look hardly different from small-leaf forms of

S. caprea. This is particularly true

for northern plants, the so-called var.

keweenawensis

Farwell, such as, for example, Bartram & Long 23745 from Nova Scotia,

Garton 6305 from Ontario, or Jesup 37 from Massachusetts. In

S. humilis anthers are larger than in

S. tristis. Also,

S. humilis has a larger range that is shifted more to the north in

comparison with the range of

S. tristis.

As it is obvious from the enclosed map,

the entire group of species that we are talking about can

be considered amphi-Atlantic. It is not represented anywhere in Asia

(except for a tiny marginal part of

S. aurita area in the Ural Mts., within the 500-mm isopluvial

line.) This group is as well absent from western North America. Hulten

(1958) has explained similar amphi-Atlantic distribution patterns by

assuming connections in the past via Beringia and East Asia. However, in

East Asia, which is generally so rich in species including primitive and

relict groups of the genus

Salix, not

a single relative of the species in question has been found. If we

accepted a possibility of direct trans-Atlantic Euro-American connections

during the period from the beginning to mid-Neogen, then we could better

explain the distribution patterns observed at present.

[List of observed herbarium specimens--S. salviifolia and S. tristis--omitted]

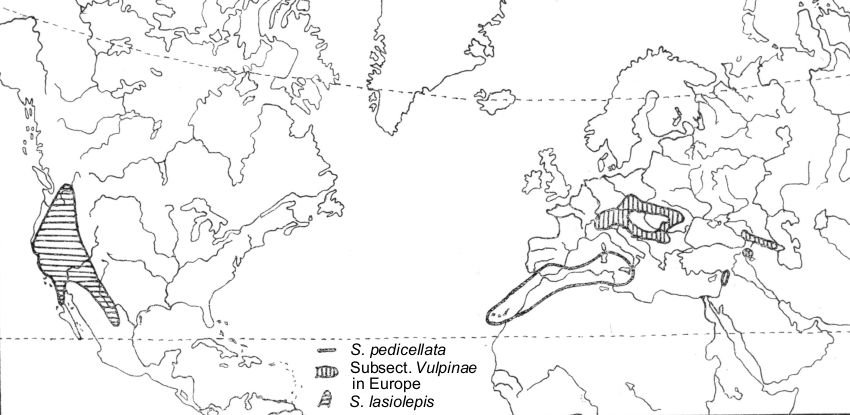

Trans-Atlantic connections of S. pedicellata Desf.

The author believes that

S. pedicellata belongs to sect.

Vetrix, subsect.

Vulpinae together with such species as

S. vulpina Anderss.,

S. silesiaca Willd.,

S. appendiculata Vill.,

S. caucasica Anderss. The close relation between the latter three

species and

S. pedicellata is

apparent, while its connection with the Far Eastern

S. vulpina is much less obvious. Together with

some other Japanese-Korean willows,

S. vulpina forms a tightly knit group within subsect.

Vulpinae.

Differently from

S. salviifolia,

S. pedicellata is a typical

Mediterranean species, according to its range. Its complete area lies

within western Mediterranean area: Sicily, Sardinia, western Spain, and

North Africa. It penetrates the eastern Mediterranean only in Lebanon and

the adjacent parts of Turkey (and probably also on some of the Aegean Is.

Subsp.

canariensis (Chr. Smith) A. Skv. is

distributed on Canary Is. and Madeira.

When looking for

S. pedicellata

relations among North American willows, we stop at

S. lasiolepis Benth. This species is widespread

in western North America from southern British Columbia to western Texas

and northern Mexico.

S. lasiolepis is

particularly frequent in California, where it is one of the most common

willows. Characters shared by

S. lasiolepis and

S. pedicellata can be summarized as follows:

-

Both species are distributed from the sea level to intermediate

and even high elevations in the mountains,

S pedicellata ascending to 800 m on Madeira and Sardinia, to

1,100 m in Lebanon, to 2,200-2,400 m in North Africa;

S. lasiolepis reaching 1,500-1,600 m in

California, 2,100-2,200 m in Mexico.

-

Both have a vast ecologic range: from alluvial habitats to

wetlands.

- Both willows are tall shrubs or trees (10-12 m tall)

with broad crowns and often rather thick trunks.

- Shoots mostly colored somewhat dirty tawny, more or

less covered with short gray felted pubescence.

-

Floriferous buds deltoid-ellipsoid, 4-7 mm long, with pronounced

lateral carinas, their tips straight (or bent toward the branch,

rarely somewhat recurved), flattened on the adaxial side.

- Stipules mostly well developed, broad, oblique,

semi-cordate, rather asymmetric.

- Petiole thick, convex above (round on

cross-section), mostly downy.

- Leaf blade shape similar to that in S. cinerea or S. atrocinerea, with the broadest part mostly above the

middle. Leaf apex obtuse or short-pointed.

- Margins in mature leaves revolute,

with more or less sparse, irregular teeth.

Glands submarginal.

- Lower leaf surface more or less covered with

pubescence, first spreading, then becoming felted; lower surface often

glabrous. Venation prominent on underside of mature leaves.

- Catkins precocious (emerging earlier than leaves);

in warm areas expanding in January-February, upright, medium-sized,

relatively slender, oblong-cylindric. Bracts rather small, hairy, with

blackish tips only or completely without black parts.

- Stamen filaments glabrous, rather short; anthers on

average 0.5-0.7 mm long.

- Ovaries medium-sized, long-stipitate, conspicuously

protruding from the bract pubescence already at the time of flowering,

mostly glabrous, gradually attenuating into short styles. Styles pass

into rather small two-parted stigmas.

It's important to note that

S. pedicellata, as regards some of its characters (such as

distribution across altitudes and latitudes, habit, floriferous bud

morphology), is closer to

S. lasiolepis than any of the European-Caucasian related species.

As for differences between

S. pedicellata and

S. lasiolepis, they may be summarized as follows:

|

S. pedicellata

|

S. lasiolepis

|

|

pronounced wood striation under bark

|

wood striation absent

|

|

leaf margin often with large teeth (like in S. cinerea)

|

leaf-margin denticles small

|

|

leaf blades rather smooth and thin, upper side opaque

|

leaf blades more or less firm, coriaceous, their

upper side smooth, more or less lustrous

|

|

bracts usually longer than broad, not truncate, with

straight hairs, which overtop bract tips by 1.0-1.5 (-2.0)

mm

|

bracts as broad as long or even broader, rounded or

truncate at tips, with rather dense, somewhat wavy hairs, which

overtop bract tips by 0.3-0.8 (-1.3) mm

|

|

stamen filaments free

|

stamen filaments often connate from

base

|

|

capsule stipes 1.5-4.5 mm long

|

capsule stipes 0.8-2.0 mm long

|

|

style 0.2-0.4 mm long

|

style length varies from 0.2 to 0.8 mm

|

S. pedicellata ssp.

canariensis is different from its continental

counterpart in weaker wood striation, longer leaves with more lustrous

upper surface, and shorter capsule stipes. Considering this character

expression, we can place this subspecies even closer to

S. lasiolepis. Besides, even within

S. pedicellata sensu stricto one can find

specimens in which wood striae are nearly absent, such as, for example,

Desfontaines' specimen preserved in LE. On the other hand, in any large

sample of

S. lasiolepis, there may be

found specimens with longer and straighter bract hairs.

In the American literature,

S. lasiolepis is usually placed in sect.

Cordatae Barr. The reason for that is,

apparently, the similarity between

S. lasiolepis and members of

Cordatae in their large-sized, glabrous,

stipitate, more or less pointed capsules. However, this type of capsules

is not unique for

Cordatae. Very

similar capsules are also found in

S. pedicellata,

S. silesiaca,

S. caucasica, the east-Asian

S. vulpina, as well as in

S. japonica Thunb.

and

S. shiraii Seemen and some members of sect.

Helix. As for the rest of the characters,

members of sect.

Cordatae are

different from

S. pedicellata in

nearly every other respect. The true members of sect.

Cordatae, both American and Eurasian,

[2]

The Eurasian sect.

Hastatae

Kern. certainly has to be identified with

Cordatae; the name

Cordatae

has the priority.

all have either straight boreal or even sub-Arctic

distribution. In southern parts of their areas, they are mostly restricted

to montane forests or

sub-Alpine and Alpine belt. The species of sect.

Cordatae are drastically different from

S. lasiolepis in the following

characters:

- young branches mostly bright colored

- floriferous buds laterally rounded, without

carinas

- stipules equilateral or sub-equilateral

- petioles flat or convex on the upper side

- leaf blades with veins slightly conspicuous or

inconspicuous on the underside

- leaf margins barely

revolute, regularly and densely denticulate

- glands truly marginal

Due to these significant differences,

S. lasiolepis should be removed from sect.

Cordatae and placed in sect.

Vetrix, subsect.

Vulpinae.

According to Schneider (1920b) and Ball (1961), a species closely

related to

S. lasiolepis is

S. irrorata Anderss., which was also placed by

these authors in sect.

Cordatae. This

opinion is completely unacceptable.

In accordance with the structure of its vegetative organs as well as

catkins,

S. irrorata has even less in

common with the species of

Cordatae

than

S. lasiolepis. However,

S. irrorata does not have much in common with

sect.

Vetrix, either. Perhaps we

should consider placing

S. irrorata

together with

S. geyeriana Anderss.

and

S. lemmonii Bebb.

S. tracyi described by Ball

(1934) in my opinion is merely a poor (probably overtopped) form of

S. lasiolepis with slenderer twigs and

thinner, scarcely pubescent leaves. It flowers later and much less

abundantly than

S. lasiolepis. When

the entire variability range of

S. lasiolepis is taken into account, differences between

S. lasiolepis and

S. tracyi, as described by Ball (1934), appear not to be

convincing enough.

Among the American willows, it is

S. hookeriana Barr. that is the closest to

S. lasiolepis. This was first noticed by

Crovello (1968). Before that

S. hookeriana had been placed together with

S. lanata,

S. barratiana, and

S. alaxensis. In comparison with

S. lasiolepis,

S. hookeriana

has thicker branches, larger buds, leaves, catkins, anthers, capsules, and

stigmas; capsules are only very short-stipitate. All these differences,

however, are purely quantitative; by no means they are contradicting the

close affinity of the two species. Apparently, the

S. lasiolepis-

S. hookeriana group should be considered a special

western-American entity within subsect.

Vulpinae.

Due to lack of herbarium material, I could not reliably clarify the

taxonomic value and position of

S. piperi Bebb. It is quite possible that this is merely a form of

S. hookeriana with weakly developed

pubescence, which was described as a species similarly to

S. tracyi, a form of

S. lasiolepis.

East Asian members of subsect.

Vulpinae --

S. vulpina and the closely related

S. sieboldiana Blume and

S. buergeriana Miq., in accordance with their morphological

characteristics, cannot be considered a link between the groups of

S. lasiolepis-

S. hookeriana and

S. pedicellata-

S. caucasica.

Similarly to the case of

S. salviifolia, the hypothesis employing a possibility of direct

trans-Atlantic early-Neogenic connections appears to be more convincing

than the more complicated assumption of a connection via Beringia and

Asia.

[List of observed herbarium specimens--S. pedicellata, S. lasiolepis,

and S. hookeriana--omitted]

References

Andersson, N. J.1858. Salices boreali-americanae.

--

Proceed. Amer. Acad. 4, Separatum: 1-32

Andersson, N. J.1868. Salix. In: De Candolle, A.P.

Prodromus systematis naturalis 16 (2): 190-323

Argus, G. W.1964. Preliminary reports on the flora of Wisconsin 51. The genus

Salix.

--

Proceed. Wisconsin Acad. Sci. 53: 217-272

Ball, C. R.1934. New or little known West American willows.

--

Univ. Calif. Publ. Bot. 17, N 14: 399-434

Ball, C.R.1947. Studying willows or making new sections in the genus Salix.

--

Rhodora 49: 37-49

Ball, C.R.1961. Salix. In: Lundell, C.L., Flora of Texas 3, part 6:

369-392

Crovello, Th.G.1968. A numerical taxonomic study of the genus Salix, section Sitchensis

--

Univ. Calif. Publ. Bot. 44: 1-61

Griggs, R. F.1905. The willows of Ohio

--

Proceed. Ohio Acad. Sci. 4: 256-314

Hulten, E.1958. The Amphiatlantic plants. Stockholm

Hulten, E.1968. Flora of Alaska and neighboring territories. Stanford

Meusel, H., Jäger, E., and Weinert, E.1965. Vergleichende Chorologie der zentraleuropaischen Flora. Jena

Pereira Coutinho, A. X.1899. Subsidio para o estudo das Salicaceaes do Portugal.

--

Bol. Soc. Broter. 16: 5-34

Schneider, C. K.1920a. Notes on American willows. IX

--

J. Arnold Arbor. 2: 1-25

Schneider, C. K.1920b. Notes on American willows. XI

--

J. Arnold Arbor. 2: 185-204

Skvortsov, A. K.1968. Ivy SSSR. Sistematicheskiy i geograficheskiy obzor [Willows of

the USSR. Taxonomic and geographic revision.] Moscow: Nauka. 262 pp.

Skvortsov, A. K.1966. Salix. In: Arkticheskaya flora SSSR [Arctic Flora of the USSR] 5.

Leningrad: Nauka. Pp. 7-118

Vicioso, C.1951. Salicaceas de Espana. Madrid

NOTES

Translation I.Kadis

31 March 2007