Present distribution and probable primary range

of brittle

willow (Salix fragilis L.)

A. K. Skvortsov

Problemy biogeotsenologii, geobotaniki i botanicheskoy

geografii. Leningrad, Nauka, 1973, pp. 263-280

Translation: Irina Kadis

Introduction

It was Andersson (1868: 209) who first came up with the idea that

Salix fragilis L. was not truly wild

and autochthonous in Europe and that it probably originated in southwest

Asia. Andersson considered another willow that he had described from

southwest Asia, S. australior

Anderss., to be a wild ancestor race of S. fragilis. This provided grounds for his hypothesis about the

Asiatic origin of S. fragilis.

However, later on it became clear that Andersson was mistaken when he

considered S. australior to be closely

related to S. fragilis. S. australior (priority name S. excelsa Gmel.) rather belongs to the cycle of

S. alba L. Therefore, the hypothesis

about brittle willow's Asiatic origin was abandoned. No further studies

were conducted in order to find out whether it was aboriginal in

Europe.

While completing the taxonomical revision of the willows distributed

within the USSR and surrounding countries, I, too, had to face the problem

with S. fragilis. The analysis of all

available material has brought me to the conclusion that S. fragilis is adventive in the USSR and Europe.

Its primary range is within northern and northeastern Asia Minor. Though

my reasoning behind the judgement on the motherland of S. fragilis is

entirely different from Andersson's, I arrived to a very similar

conclusion. Even though I have already presented it in the review of the

willows of the Caucasus and Asia Minor and also in the review of the USSR

willows (Skvortsov 1966: 116-117; Skvortsov 1968: 68, 111-113.), detailed

arguments were beyond the scope of these works. The purpose of the article

is to provide this argumentation.

I used the herbarium material at most major depositories in this

country: herbaria of the botanical institutes in Leningrad, Kiev, Tbilisi,

Baku, and Yerevan; Moscow and Tomsk university herbaria; and also the

Herbarium of the Natural History Museum in Lvov. Of foreign depositories,

I examined all the material at the Prague National Museum and collections

from Asia Minor at the Royal Botanic Garden in Edinburgh. I express my

cordial gratitude to all the colleagues who run collections at these

institutions. I wish to thank Dr. E.L. Swann (Norfolk, England) and Dr.

A.R. Pinto da Silva (Oeiras, Portugal) for some valuable material they

mailed for the study. I am indebted to Dr. Neumann (Vienna) for his

important comments on the distribution of S. fragilis in Western Europe.

The late E.I. Steinberg provided translations of Estonian texts.

I have conducted field observations primarily in Moscow, Smolensk,

Kaluga, and Tula oblast's. Later on I included the vicinity of Leningrad,

the Carpathians, and Volgograd Oblast. Additionally, I conducted some

observations at a lesser scale in Pskov, Novgorod, Ryazan, Voronezh,

Saratov, Belgorod, and Kiev oblast's, and also in Latvia and central

German Democratic Republic. Literature data were extensively used as

well.

I. Brittle willow in central European Russia

Here is what Tsinger (1886: 393) said about S. fragilis in his

Anthology of Knowledge:

"It is very common everywhere along rivers, around ponds, at dams,

near dwellings, and at roadsides; for Tver Government it is listed only as

cultivated. It probably becomes rare in the southeast, in the proximity of

the Volga banks." This description was inherited by the early editions of

Mayevskiy's Flora of Central Russia (1892: 413; 1895: 435; 1902: 469). The

note regarding Tver Government found in Tsinger (1886) as well as the

first three editions of Mayevskiy's Flora, had been originally made by

Bakunin (1879: 348).

Petunnikov (1901: 37-39), citing mostly F.A. Teploukhov's opinion

(Teploukhov apparently never published the results of his willow studies),

stated that the majority of samples treated as S. fragilis within Moscow Government were actually the so-called

S. viridis Fr., i.e., hybrids of

S. fragilis and S. alba. At the same time, according to

Petunnikov, the true, non-hybrid S. fragilis

was rather rare in Moscow Government. Remarkably, all of

non-hybrid specimens of S. fragilis

that Petunnikov was aware of turned out to be staminate. Siuzev (1901) was

another author citing Teploukhov's opinion on the hybrid nature of most

S. fragilis in this country. He

provided quotations from a letter by Teploukhov, which even indicate that

Teploukhov probably had doubts about the aboriginal nature of S. fragilis. At the same time, Siuzev argued

that indeed he himself had found pistillate specimens of S. fragilis on

the Oka River in Moscow Government, and therefore Teploukhov finally

agreed that S. fragilis was a native

species in the flora of this country.

Syreshchikov (1907: 15, 19; 1927: 98, 99) noted in support of

Petunnikov's view that S. viridis was

common in Moscow Government, while S. fragilis was rare. The Flora of Central Russia by Mayevskiy,

starting from edition 4 (1912: 500), also says that "crosses with

S. alba occur more often than the

typical" S. fragilis; while the note

about Tver Government vanishes from the text. Starting from that time, the

suggestion that S. fragilis might be

not native in central European Russia is not repeated in the

literature anymore. It is not found in the regional "floras" of Vladimir

and Kaluga (Flerov 1902, 1912), Tula (Rozen 1916), or Kalinin (Nevskiy

1952).

My own observations in central European Russia completely support

the conclusions of the earlier authors about domination of hybrids

S. fragilis x S. alba over "pure" S. fragilis. Though the two species belong to the same section,

they have a number of quite distinct differences. Therefore, recognition

of hybrids should not be just an intuitive procedure based solely on

inspiration, asâalas!âit often happens. Instead it can be

based on distinct morphological criteria.

The diagnostic characters of the two species are superposed here

below.

|

S. fragilis

|

S. alba

|

|

Trees developing in the open produce

low, nearly spherical crowns; large oblique limbs originate at a

fairly low level

|

Crowns of trees developing in the open

mostly elongate; trunks upright, tall; limbs relatively

short

|

|

Within old part of crown, 1-3-year-old

branches never pendulous, spreading at 60-90° angles, breaking off easily when gently

pressed

|

Within old part of crown, 1-3-year-old

branches often pendulous, growing at angles less than 60°, not as

brittle

|

|

It is only current-year branchlets,

particularly suckers, that often become pigmented red or rich

brown; older branches within old crown uniformly yellowish-gray or

nearly ivory, occasionally with some orange tint or reddish

spots

|

Current-year branchlets mostly green;

older branches becoming rather bright reddish or brownish,

pigmentation more pronounced on the lighted side

|

|

Current-year branchlets may be

puberulent; older branches always completely

glabrous

|

Current-year branchlets always

pubescent; older branches mostly pubescent, at least in distal

parts

|

|

Buds during late fall and winter colored

same as branches; apices blackening due to bud scale dieback. Buds

ovoid to lanceoloid, more or less acutish, abaxially convex or

more or less carinate; slightly convex or sometimes also carinate

on adaxial side

|

Buds during the fall and winter colored

same as branches or brighter, not blackening,

oblong lanceoloid, mostly blunt, abaxially

somewhat convex; mostly completely flat adaxially

|

|

Outermost leaf primordium in bud mostly

pale or grayish brown, broad, nearly round when spread, with

several parallel veins originating from base. Catkin primordia in

floriferous buds densely sericeous

|

Outermost leaf primordium mostly

reddish, oval, its venation pinnate. Catkin primordia in

floriferous buds puberulent, greenish; imbricate bracts form

distinct pattern visible through pubescence

|

|

Young leaves in spring light

yellowish-green; mature foliage dark green, without bluish

tint

|

Young leaves more or less deep

bluish-green; mature leaves pale bluish-green or

sericeous

|

|

Stipules obliquely semi-cordate,

distinctly inequilateral

|

Stipules narrowly lanceolate,

linear-subulate, subequilateral, rarely somewhat

falcate

|

|

Petioles 7-15 mm long; petiolar glands

pronounced in all leaves on the branch, except for proximal ones

|

Petioles 2-8 mm long; petiolar glands

pronounced mostly only in distal leaves and on suckering

shoots

|

|

Young leaves mostly completely glabrous,

occasionally sparsely hairy; mature leaves glabrous

|

Young leaves delicately sericeous;

mature leaves also more or less silvery pubescent

|

|

Leaf blade broadly cuneate or rounded at

base; reticulation network very conspicuous on underside. Margin

dentation rather coarse, denticles mostly bent or rounded. Stomata

on upper leaf surface mostly sparse or wanting

|

Leaf blade mostly cuneate at base; only

major lateral veins are visible on underside, reticulation

wanting; margin minutely serrulate, denticles mostly acute.

Stomata dense on upper leaf surface

|

|

Catkins spread nearly at right angle

from branch. All flowers open simultaneously in staminate

catkins

|

Catkins positioned at acute angle on

branch. Proximal flowers in staminate catkins open earlier than

distal

|

|

Bracts 0.8-1.5 x 0.5-0.8 mm, covered

with straight trichomes that extend by 0.8-2.0 mm beyond bract

margin. Bracts remain pale on drying

|

Bracts 1.2-2.8 x 0.7-1.0 mm,

puberulent; trichomes extend by 0.2-0.6 mm beyond bract margin.

Bracts turn rusty-brown on drying

|

|

Filaments pubescent only at base (along

â

to ž of their length); dry anthers 0.5 (0.6) mm

long

|

Filaments pubescent up to ž-Â― of their

length; dry anthers (0.5) 0.6-0.7 mm long

|

Hybrids occupy and intermediate position, being closer to one or the

other parent as regards characters expression. This variability is

understandable, as we deal not only with F

1

generation, but various products of segregation formed as a result of

reciprocal crosses with parental species as well as crosses within

F

1. Heterosis is typical for the majority of

hybrids. Usually hybrids grow faster and produce more robust branches than

parents

[1]Some authors, for example, Nazarov (1949: 54) have had an

impression that pistillate plants of S. fragilis tend to grow faster than staminate. Such

observations without doubt have to be attributed to comparisons of

hybrid pistillate and non-hybrid staminate specimens..

There also exist hybrids of S. fragilis with S. pentandra

L. and probably with S. triandra L.;

however, those are rare in central European Russia and present no interest

for this discussion.

Differently from Siuzev's experience, my search did not yield any

clearly non-hybrid pistillate S. fragilis around the Oka River or elsewhere in central European

Russia. Trees displaying typical species characteristics were invariably

staminate. More than that, the herbarium search within material from this

area yielded the same result: not a single pistillate specimen was found

without hybrid traits. One could speculate that we are dealing here with a

case of sexual dimorphism, i.e., pistillate plants are characteristically

different from staminate ones in many respects. However, this assumption

does not stand under scrutiny, as pistillate S. fragilis are found in other parts of the area, where they are

similar to staminate plants in every respect (except for their sex).

Siuzev's statement about presence of "pure" pistillate S. fragilis at the Oka River was apparently

based on insufficient character analysis.

The predominance of hybrids along with complete absence of

non-hybrid pistillate specimens in such a wide-ranging species as

S. fragilis within the central

European Russia presents a puzzle that needs explanation. It is Bakunin's

opinion that comes to mind first. He believed that within Tver Government

all of S. fragilis was just

cultivated. However, brittle willow in Moscow, Kaluga, Smolensk, Tula, and

Ryazan oblast's is commonly found in habitats were it sure could not have

been planted. In the aftermath of a storm or during a windy day,

multitudes of broken twigs are found around every old brittle willow. Many

branchlets are carried away by wind or running water and root in 2-3

weeks, if they happen to be in favorable moisture situations. Thus

S. fragilis is a spontaneous species

undoubtedly belonging to the wild flora. However, does it also happen to

be indigenous? In order to answer this question, it is necessary to

consider habitats taken by the species and decide whether there exists a

niche for it anywhere in undisturbed nature.

For solving a problem of this type, historic records also might be

of some value; however, in this case chances of finding positive evidence

are more than slim. Besides, historic evidence can be only relatively

meaningful. If we cannot provide documentation describing the introduction

of potatoes to Kamchatka, that does not necessarily mean that potatoes are

native there. On the other hand, even though we know for sure that grapes

have been cultivated in Tajikistan for ages and even millennia, we still

cannot exclude a possibility for wild species to exist there. Whether or

not we discover indications of oriental plane cultivation in the Varzob or

Tsav river valleys, the outcome is not going to alter the fact that plane

is a member of the native flora in Armenia. In all such cases, we should

base our conclusions first and foremost on biological observations.

Outside truly secondary, man-made habitats, such as roadsides,

ditches, or residential lots, S. fragilis has been found along streams and rivers, in damp

depressions, and in small spring-fed fens. The most common willows on

river banks in this country are S. viminalis L., S. dasyclados

Wimm., S. triandra L., and S. alba L. There is no doubt that these four are

native to the area. Whenever there appears a freshly deposited alluvium

patch in a river valley, it is promptly taken by these species. It is

mostly S. viminalis that occupies

sandy deposits right along the water margin; S. triandra and S. dasyclados

both require silt deposits and thus settle particularly along slow creeks

or surface run-off depressions; still more often all the three species

form mixed thickets in various proportions.

As for S. alba, it favors

sandy-silty deposits that are formed during large floods at high levels,

which remain dry during most of the year. Depressions that remain moist

for a long time after the flood are particularly favorable. Thus it forms

pure or nearly pure stands in large river valleys, usually producing small

and dense, even-aged groves extended along river beds. Most of these

groves have been clear-cut; however, I have found some along the Oka and

Protva that were quite intact. When S. alba happens to grow along small streams, it is usually only

solitary and, as a rule, occurs not far from some large river

valley.

S. alba, S. viminalis, S. dasyclados, and S. triandra

are consistently found at suitable habitats in semicultural landscapes as

well as in those only moderately affected by human activities. The less

the landscape has been altered by humans, the more the original ecological

preferences of each species are pronounced, and the more often we

encounter good seed reproduction at appropriate habitats.

In contrast to the species named above, S. fragilis never forms continuous single-aged groves in large

river valleys, particularly along the Oka. We always find only scattered

solitary trees of different ages that randomly occur in different parts of

river valleys, most often within the floodplain, around oxbow lakes, along

small tributaries, or in erosional depressions formed by floods. These

habitats are also preferred by S. alba, which naturally grows there. Healthy natural groves of

S. alba never contain any S. fragilis, even as a minor admixture. In

undisturbed situations, all habitats suitable for S. alba become colonized by S. alba only, even though there are fruiting

hybrids S. alba x S. fragilis growing in close proximity. These

hybrids along with pure S. fragilis

are encountered only in habitats fairly disturbed by humans. Hence, when

natural habitats favorable for S. alba

are available, hybridization between S. alba and S. fragilis,

however extensive it is, has no effect on the integrity of S. alba, its ecological and morphological

stability as a species. It is only S. fragilis that is subject to disruption and erosion as a

species.

During my tours of the major rivers (Oka, Moskva, Protva, Ugra,

Osetr, and Upper Dnieper), I have never encountered any large-scale

reproduction of S. fragilis or its

hybrids. Consequently, we should admit that within the major river valleys

in this country there are no habitats where S. fragilis could exist prior to human disturbance.

Yet what about those small rivers, brooks, and spring-fed fens?

Perhaps S. fragilis could be a natural

part of plant communities or successions there, could not it? All of our

native forest trees, including those that never dominate climax formations

or major successional stages, are constantly found (even though they might

be scarce and depressed) in the oldest, minimally disturbed forests. This

is not the case with S. fragilis. It

is not consistently present in any climax communities, even as a rare

species, neither found regularly at any particular successional stage.

Stream banks and moist bottoms of depressions in this country used to be

naturally covered by black alder groves and stream-bank spruce

associations. We cannot imagine a light-loving tree with a broad low

crown, such as S. fragilis, growing

amidst a dense spruce forest or black-alder grove. It could not even

temporarily be present during the natural regeneration stages of these

communities.

Openings in black-alder groves and spruce forests that occur due to

wind or insect damage never affect the forest environment to such a

significant extent that it ceases being a forest; and S. fragilis never trespasses forest habitats, as

far as we know from observations. Whenever moist forest grounds start

receiving more light, tall herbs would conquer the spot along with

S. caprea L., S. aurita L., and sometimes S. cinerea L., yet never S. fragilis. It is only present in the

situations when light has been available for a long time and forest

character of the habitat has been long lost to a large extent. It is only

then that S. fragilis may settle,

self-dispersed not from seed, but rather from broken twigs brought in by

wind or water.

We should conclude that within the natural vegetation cover of

central European Russia there is no niche for S. fragilis to occupy. We thus have to acknowledge that brittle

willow is an adventive plant in this area.

II. Brittle willow in other regions of the USSR (excluding the

Caucasus)

Many "floras" and reviews (Wolf 1900: 21; Seemen 1908-1910: 70;

Nazarov 1936: 203; Pravdin 1951: 168; Rechinger 1957: 67, and others)

inform that S. fragilis is distributed

across the entire European territory of the USSR, except for the extreme

north, and that its range also extends to West Siberia and the Altai Mts.;

some believe that this willow even reaches the Lake Baikal (Penkovskiy

1901: 62). However, herbarium data signify that S. fragilis (together with its hybrids) hardly

crosses the Volga. East of the Volga, it is represented only by

some solitary findings. I have seen five specimens from Siberia and

Kazakhstan (Biysk, Alma-Ata, Akmolinsk, Karaganda, and Telmanovo in the

vicinity of Tselinograd) and some very scarce from the southern Urals and

Bashkiriya. A single concrete reference to S. fragilis from the Altai Mts. (Edzhigan ValleyâKrylov) has

turned out to be a misidentification (Skvortsov 1956).

The notion of predominance of hybrids S. fragilis x S. alba over

"pure" S. fragilis was extrapolated

over the entire range of this species within the USSR by Nazarov (1936) in

the Flora of the USSR. However, a detailed herbarium study and

differential mapping suggest a more intricate and interesting relationship

between hybrid and non-hybrid S. fragilis. Remarkably, all of the named five specimens from

Siberia and Kazakhstan happened to be hybrids. Specimens from Alma-Ata and

Biysk are known to be collected from cultivated plants. The remaining

three samples from Kazakhstan originate from regions where S. alba is not distributed, which makes the

formation of autochthonous hybrids impossible. Apparently, these were also

collected from cultivated plants.

Non-hybrid S. fragilis was never

ever collected from the Urals or Upper Vyatka Basin, neither from Volga

Uplands. Hybrids of S. fragilis are

not infrequent in Saratov and Volgograd oblast's, even away from human

dwellings, where they appear to be growing naturally. However, a more

careful examination always shows they have been planted. Apparently, in

the Volga Basin there is no current advancement of S. fragilis hybrids, neither by seed

dissemination, nor even from vegetative parts.

Further herbarium study has shown that the entire periphery of

brittle-willow range within the European USSR has been occupied by hybrid

plants only. "Pure" S. fragilis occurs

only eastward, i.e., east of the line connecting Vyborg, Volkhov, Uglich,

Vladimir, Arzamas, Tambov, Voronezh, Kremenchug, and Beltsy, with an

isolated locus on the Crimea Peninsula.

According to Meinshausen (1878: 314), around St. Petersburg,

S. fragilis "occurs only in

cultivation, though some plants are occasionally found here and there in

the woods, apparently as escapees from cultivation, as they are always

only staminate." Aun (1939: 43-47) remarks that in Estonia there is no

wild S. fragilis, either. All the

specimens that Aun had found blooming (in PÃĪrnu, VÃĪrru, Tartu, and Pechory

in the vicinity of Pskov) happened to be staminate. He was unable to

locate any pistillate plants despite his deliberate effort. Even local

forest rangers were unable to point to any pistillate brittle willows in

response to official requests through the Forestry Department. On the

other hand, hybrid specimens, though not too common, were encountered in

Estonia, and among those were some pistillate plants. My own observations

around Leningrad and the herbarium studies fully support the reports by

Meinshausen and Aun. I conclude that in Estonia and around Leningrad, the

distribution of brittle willow is similar to what is observed around

Moscow. The same refers to Pskov and Novgorod vicinities.

I have not found opinions similar to Meinshausen's or Aun's in the

literature referring to other regions. However, according to the herbarium

analyses, the area that harbors staminate non-hybrid plants only and where

pistillate trees are lacking is actually considerably wider. It extends

westward about to the line connecting Ventspils, Vilnius, Mogilev, Kiev,

Zvenigorodka, Vinnitsa, Chernovtsy, and Kluzh. Non-hybrid specimens of

both sexes can be found only west of this line. Therefore, if at all there

are any native, primary habitats of brittle willow in Europe, it makes

sense to look for them only west of this line. Apparently this boundary

reveals the central-European distributional pattern of S. fragilis, and since the flora of central

Europe is best represented within the USSR in the Carpathians and

Transcarpathia, first and foremost one should search for primary habitats

there.

I made two attempts to find such habitats during my trips to the

Carpathians in 1957 and 1968; however, both were unsuccessful. Brittle

willow is very abundant in the Carpathians. Occasionally (e.g., along a

small river named Khustinka), I encountered populations with considerable

individual variability among plants that appeared to be the "pure"

species, â an evidence of normal seed reproduction. S. fragilis even occurred continuously for a few

kilometers along some small streams, such as the Lyuta River, the left

tributary of the Uzh.

However, in intact habitats where the virgin vegetation was more or

less preserved, there was evidently no room for S. fragilis. In narrow gorges, the tall forest

usually descended right to the banks of small rivers, allowing only

minimum growth of alder and some S. purpurea L. or tall herbs here and there. At the same time,

intact habitats on the banks of a large river (Tissa R.) were taken by

pure groves of S. alba, much like in

the central European Russia. There is no doubt left for me that S. fragilis is an adventive tree in the Carpathians

and Transcarpathia, though it now appears to be well naturalized at some

places there .

III. Brittle willow in Europe

Due to lack of observations and herbarium material, my analysis of

brittle willow distribution in Western Europe has to be based largely on

literature sources.

According to many respectful sources (Hjelt 1902: 86; HultÃĐn 1950:

144; Lid 1963: 251; Hylander 1966: 288), S. fragilis is an introduced

species found only in cultivation on most of Scandinavian territory,

except for extreme southern Finland, southern Sweden, and Denmark, where

it also known to escape from cultivation. In Scandinavia hybrids with S.

alba are not infrequent (described as S. viridis Fries 1928: 283). These hybrids, along with S. alba itself, also are either cultivated or

feral.

According to the author of a monograph on the British willows,

Linton (1913: 14), S. fragilis is

native in England, southern Scotland, and Wales, being introduced to

northern Scotland. According to Praeger (1934: 26), it is probably

introduced in Ireland. A more recent British source (Clapham et al. 1962:

590) depicts the same view. However, the actual situation with S. fragilis on the British Isles appears to be

quite different. Descriptions provided for this species by all

authoritative English sources (Loudon 1838: 1516; White 1890: 348; Elwes,

Henry 1913: 1754; Linton 1913: 14; Moss 1914: 17; Clapham et al. 1962:

590) clearly demonstrate that all the authors actually present hybrids

S. fragilis x S. alba under the name "S. fragilis." Characteristically, Linton (l.c.)

provided a synonym name S. russeliana

Sm. for S. fragilis. As a matter of

fact, S. russeliana has been long

recognized as a hybrid even in the western literature (Wimmer 1866: 133,

and others). The same conclusion is to be reached when one considers

identifications on herbarium specimens provided by the English.

Along with S. fragilis, the

British authors also list S. decipiens

Hoffm. Some (White 1890: 348) consider it to be a hybrid of S. fragilis and S. triandra; others (Linton 1913: 17) think of it as a subspecies

of S. fragilis. Some refrain from

interpreting this taxon (Clapham et al., l.c.). According to Linton and

the latest Flora (Linton l.c., Clapham et al. l.c.), S. decipiens appears to be found only in

cultivation, sporadically, and infrequently in Britain. Reliable

references exist only for staminate specimens. The study of Hoffmann's

authentics of S. decipiens ("S. decipiens mihi. Erlangae" LE!) as well as

material identified by the British as S. decipiens shows that all of these are actually true S. fragilis. Therefore, the situation with

S. fragilis on the British Isles is no

different from what we find around Moscow and Leningrad.

Though S. fragilis and its

hybrids are distributed all across the British Isles, there is a distinct

increase in density in the southeastern England, as it is shown in the

Atlas of the British Flora (1962: 188). This is the most continental

part of the British Isles; in those areas where the Atlantic flora

dominates, S. fragilis becomes

scarcer.

According to Coutinho (1939: 189), S. fragilis is scattered all across Portugal, both cultivated and

"nearly wild" ("subespontaneo"). However, the local Flora (Rozeira 1944)

of Tras-os-Montes, one of the largest provinces, does not list this

willow. Of those four specimens that I received from Portugal under the

name "S. fragilis," two (M. da Silva

2724; Rainha 5706) appeared to be hybrids with S. alba, and the other two had no relationship to S. fragilis (Rainha 5930âprobably a

puberulent variation of S. alba; M. da

Silva 2432âS. babylonica or its

hybrid.)

In his monograph of Spanish willows, Vicioso (1951: 47), citing

Laguna (1883), provides that S. fragilis is found both wild and cultivated on most of the

territory, though it is hard to tell autochthonous specimens from

introduced, as it is always the case with plants cultivated from olden

times. Apparently the author is not at all convinced that this willow is

native in Spain. Merino (1906: 616) states that S. fragilis is definitely only a cultivated

plant in Galicia. The description and illustration in Vicioso's monograph

do not depict all characteristic features of S. fragilis. Most probably, hybrids S. fragilis x S. alba have

been actually described in Spain as S. fragilis. Remarkably, GÃķrz (1929: 15) believed that S. fragilis does not grow on the Iberian

Peninsula, but is substituted there by S. neotricha Goerz, which resembles S. australior Anderss. (= S. excelsa Gmel.) from the Caucasus. Obviously, S. neotricha is yet another designation for the

same hybrid cycle S. fragilis x

S. alba. In any case, there is no talk

about autochthonous S. fragilis

existing on the Iberian Peninsula.

Major sources report S. fragilis

to be distributed across "nearly the entire" France (Camus 1904: 76; Coste

1906: 271; Rouy 1910: 193); however, according to Bonnier (s. a.; ca.

1930: 40), S. fragilis is not found in

western, southwestern, and Mediterranean France. Neumann, a contemporary

Austrian authority on willows, believes, mostly basing on own

observations, that S. fragilis no

longer grows around Paris (Neumann in litt. a. 1962). According to

Chassagne (1956: 260), in the French Massif Central S. fragilis is often cultivated, and it is hard

to tell whether it is growing there naturally. Chassagne believes that the

species has an oriental origin and advances due to cultivation. Thus we

can hardly suggest that S. fragilis is

aboriginal in France. As for hybrids with S. alba, they are not infrequent. According to Chassagne (1956:

259), these hybrids are found even more often than the parental

species.

Buser (1940: 629) considered S. fragilis "by far, the rarest of all willows" in Switzerland.

According to Buser, "true S. fragilis

... is just as rare, as hybrids S. alba x S. fragilis are

common in Swiss piedmont. So it is not surprising that the Swiss have been

taking hybrids for the species or at least have not been distinguishing

between the species and hybrids... Nearly all of "S. fragilis" in local Swiss "floras" are

actually hybrids. This situation can only be explained if we admit that

S. fragilis as well as its hybrids are

not native, but rather introduced" (Buser 1940: 631). The recent Flora of Switzerland (Hess et al. 1967: 666), which includes Tirol, the French

Jura Mts., and Savoy, treats S. fragilis as an introduced species within the entire

area.

The Italian researcher of the 19th century Bertoloni (1854: 303)

reported S. fragilis for Palermo only.

Later authors believed it was scattered all across Italy (Parlatore 1867:

220; Borzi 1885: 138; Fiori 1923: 341). However, local "floras" portrait

S. fragilis as a random alien species

that shows no affinity to any particular region or native plant community.

Thus in Verona this "rare, random" tree is known from a single location

(Goiran 1898: 19). For Triest (Marchesetti 1896-97), Reggio-Emilia and

Modena (Negodi 1944), as well as the Silagian Mts. (or La Sila) in

Calabria (Sarfatti 1959) S. fragilis

is not at all listed. It is known from just a single locality in the Roman

Apennines (Zangheri 1966: 86) and a single place within Teramo Province

(Zodda 1954: 66). For the Sicily (Lojacono 1904: 392), it is only the

hybrid S. alba x S fragilis that is mentioned; besides, the vague

description makes one suspect that forms of S. alba are described instead. There are more examples like this.

Hence in Italy S. fragilis is not

aboriginal, either.

In Austria and Germany most authors interpret S. fragilis as a common species growing in

natural habitats. However, in these countries, as well as in Britain,

Switzerland, and others, hybrids of S. fragilis and S. alba have

habitually been taken for S. fragilis.

A series of hybrid forms have been described under binary names: S. rubens Schrank 1789: 226; S. fragilissima Host 1828: 6; S. palustris Host 1828: 7; S. excelsior Host 1828: 8. Even though Wimmer

(1866: 133-134) had pointed to their hybrid nature, K. Koch, an authority

in German dendrology, included them all in S. fragilis (1872: 514). The German-Swiss Synopsis (W. Koch

1907: 2300), similarly to the English sources, designated the true,

non-hybrid S. fragilis as "var.

decipiens," while noting that it was

known perhaps only in cultivation. Hartig (1851: 563) remarked that

S. russeliana Sm. (that is, a hybrid)

was common in northern Germany, while non-hybrid S. fragilis was so rare there that he had only

seen it in botanic gardens. According to Toepffer (1914: 191), in Bavaria,

all records for S. fragilis needed

revision due to constant mixing with hybrid plants. As per Toepffer, the

true S. fragilis (which he as well

named "var. decipiens") was rare in

Bavaria. In Wurttemberg, according to Bertsch (1951: 46), only hybrids

were encountered, all of them originating from cultivated specimens. In

the Northern German Lowlands, non-hybrid S. fragilis was reported rare and even completely missing from

many areas (GÃķrz 1922: 31). Neumann (in litt.) also believes that

S. fragilis is not present in the

western part of Northern German Lowlands and beyond, in the

Netherlands.

During the fall of 1964, I found some small scattered non-hybrid

S. fragilis growing along small

streams in the Gartz southern piedmont. These habitats appeared to be

completely similar to those occupied by this willow within this country:

in the Carpathians and even around Smolensk and Moscow. I also found

hybrids in-between Halle and Jena. The herbarium material from Germany that I

had at my disposal contained a number of non-hybrid as well as hybrid

specimens of both sexes. I concluded that within the southern GDR and

central BRG the situation with brittle willow is similar to that in the

western regions of our country, that is, the tree has been nearly

completely naturalized, so that occasionally it appears as a native. At

the same time, in the northwest and southwest the status of brittle willow

is closer to that in France and England.

In Lower Austria, S. fragilis

used to be considered as "one of the most common willows, particularly in

the Danube Valley" (Kerner 1860: 185). However, later on Rechinger (1957:

67) remarked that all of S. fragilis

from the Danube were actually hybrids.

In Belgium, S. fragilis has been

known as mostly cultivated, its hybrids encountered much more often than

the species (LawalrÃĐe 1952: 36).

In Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, and Romania, S. fragilis appears to be frequent. It is

usually mentioned in "floras" as a native tree. However, it is hardly

possible that the origin of S. fragilis in Romania and Czechoslovakia could be drastically

different from its origin in our Carpathians; or else that the situation

in Poland fundamentally differs from what takes place in Germany or the

Baltic States. Even though non-hybrid plants of both sexes are not

infrequent, the majority of specimens are of hybrid nature, as per

WoÅoszczak (1889: 292), for Transylvania or Szafer (1921: 33), for

Poland.

In Yugoslavia, S. fragilis has

been believed to be widespread (Beck von Managetta 1909: 115;

Adamoviħ 1909: 194; Rohlena 1942: 19; Å panoviÄ? 1954;

JovanoviÄ? 1955; Em 1967; and others). However, a note by Hirc (1904:

158) remarkably testifies for absence of herbarium collections from

Croatia. S. fragilis is also characteristically absent from remote ravines

in Macedonia, where the flora should still be most primeval (SoÅĄka

1938-39). Those few specimens from southern Yugoslavia that I examined

were all hybrids.

Velchev (1966: 56) reports S. fragilis being distributed in Bulgaria "across the entire

country." However, the description that he provides rather fits hybrids.

According to Stefanov (1943), S. fragilis in Bulgaria is a boreal element restricted to the

northwest. According to Chernyavskiy et al. (1959: 94), stands of

S. fragilis in Bulgaria are of

"secondary origin." Regretfully, this statement is elaborated no

further.

In Greece S. fragilis apparently

is completely absent.

While summarizing data on S. fragilis range in Europe outside the Soviet Union, we can

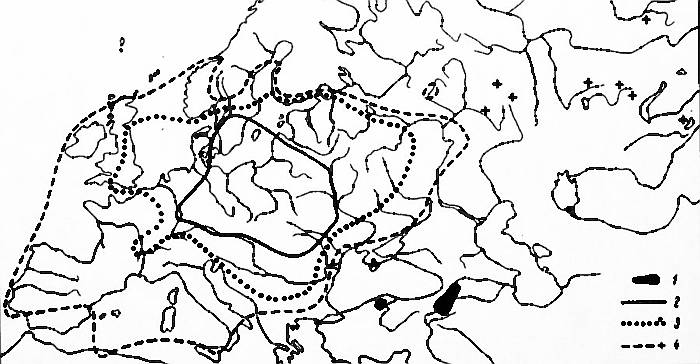

distinguish the same three zones as within the Soviet Union (Fig.

1):

* core zone where S. fragilis

has been nearly entirely naturalized and is represented by non-hybrid

trees of both sexes;

* transitional zone, where the species is still quite common,

though among non-hybrid plants staminate ones overwhelmingly

dominate;

* peripheral zone, where virtually only hybrids are represented,

being scattered, sporadic, or cultivated only.

Of course the demarcation lines are at this point very much

approximate. For the refinement, much more information is needed than I

have had at my disposal.

Fig. 1. Distribution of Salix fragilis L.

1. primary range

2.

area where S. fragilis is nearly

naturalized, non-hybrid plants of both sexes encountered

3. distribution limits for non-hybrid staminate plants, their

reproduction spontaneous, vegetative

4. boundary of area where nearly

exclusively hybrid plants are encountered, originating from

plantings

Literature sources also report a rather large-scale introduction of

S. fragilis to North America, where it

appears to be also nearly naturalized. All those specimens from North

America that I have examined happened to be only hybrids.

IV. Brittle willow in the Near East, Asia Minor, and the

Caucasus

In eastern Asia Minor, southern and eastern Transcaucasia, Iran, and

the Soviet Central Asia there is a common, widely distributed willow,

S. excelsa Gmel. This species is a

race of S. alba, closely related to

it, though distinct in a number of characters that resemble S. fragilis: non-weeping crown, stout, brittle

branches, stout buds, less pubescent leaves and branchlets, and more

pubescent bracts. It was first described from northern Iran in 1774 by

Gmelin, the younger, but then forgotten and described for the second time

by Andersson (1867: 43) as S. australior Anderss. or S. fragilis Îī australis

(Andersson 1868: 210). Andersson placed this tree in the S. fragilis cycle by mistake and then suggested

that the European S. fragilis had

originated from southwest Asia (Andersson 1867: 41).

Relying on Andersson's works, Boissier (1879: 1184) also listed

S. fragilis for Syria, Asia Minor, and

Transcaucasia. However, it soon became evident that S. australior Anderss. was not at all a form of

S. fragilis, but rather belonged to

S. alba cycle. Despite this

clarification, due to the authority of Boissier, almost until recently

S. fragilis has been considered an

"oriental" species present in Syria and Lebanon (Bouloumoy 1930: 316; Post

1933: 530); Jordan (NÃĄbÃĐlek 1929: 24); Iran (Parsa 1950: 1351); western

and southern Transcaucasia (Medvedev 1883: 228, Nazarov 1936: 203);

Dagestan (Lvov 1956: 77); the western and eastern Caucasus (Makhatadze

1961: 51); and the Russian Central Asia (Fedchenko 1915: 295, Protopopov

1953: 36). There is no doubt that all these listings were based on either

erroneous identifications or uncritical borrowing.

Meanwhile, the true S. fragilis

was actually discovered growing in the East. It was quite wild, neither

adventive, nor deliberately introduced, its populations represented by

both sexes. Besides, hybridization with S. alba was completely absent or at least very insignificant. It

was first collected in 1892 by Sintenis; however, the first reliable

record of S. fragilis in Asia Minor

belongs to GÃķrz (1930: 113). He discovered specimens collected by S.

Turkevich in former Kars [Province of Turkey; Russian Turkestan at the

time of collection]. Even though GÃķrz considered this find "amazing, " he

still under-evaluated its importance. It did not even occur to him to

re-examine the collections he had at hand. Indeed he failed to correctly

identify some true S. fragilis that he

collected himself.

I examined the following specimens of S. fragilis from its eastern range:

1. Paphlagonia, wilajet Kastambuli, Tossia, Utsch-tschesme,

3.VI.1892, P. Sintenis No. 4089, fl. femin. et fol.;

2. districtus GÞmÞsch-hane, supra Bayburt, 1500 m, frutex inter

stirpes typicas S. australioris idque

prorsus sponte nascens, 8.VI.1931. R. GÃķrz (Sal. Asiat. No. 37: "S. australior var. pseudofragilis Goerz var. nova"), fol.;

3. inter GÞmÞsch-hane er Bayburt, 1600 m, sponte nascens,

16.VI.1931. R. GÃķrz (Sal. Asiat. No. 37-a: "S. australior ad var. pseudofragilem Goerz vergens"), fl.

femin.;

4. Prov. Kastamonu, 10 km from Daday to Effani, 900-1000 m,

stream-side in pinetum, 30.VII.1962. Coode et Yaltirik No. 38610,

fol.;

5. Prov. Kastamonu, between Seydiler and Kure, 1200 m, salix scrub

near stream, 30.VII.1962, P. Davis No. 38464, fol.;

6. Karsskaya obl., bliz st. Promezhutochnoi, bereg r. Kyaklik [Kars

Oblast, close to Promezhutochnaya Station, bank of the Kyaklik

River], 11.V.1914, S. Turkevich No. 245, fl. femin., masc.;

7. Karsskaya obl., mezhdu Sarykamyshem i Karakurtom v Tyaklitskoi

balke [Kars Oblast, between Sarikamis and Karakurt in the Tiyaklit

Depression], T. Roop, fol.;

8. Sanjak Erzerum, tugai r. Khnys-chai bliz Khnyskaly [Erzurum

Province, Hinisçayi River forested floodplain near Hiniskaly],

14.VII.1916, V. Sapozhnikov and B. Shishkin, fol.;

9. bliz Akhaltsikha, r. Poshov-chai [near Akhaltsikhe, the

Posof-çayi River], 9.VIII.1920, D. Sosnovskiy, fol.

The latter is the only sample known so far from the USSR

territory.

There is no indication that any of the listed specimens originate

from cultivated plants. Accompanying hybrid series, which are so common in

European collections, are absent here. Indeed hybrids (T. Roop 1911, LE)

were collected only around the Kars Fortress, from the landscape that had

been greatly disturbed for a long time.

According to Grossheim (1945: 27), S. fragilis is commonly cultivated in the Northern Caucasus. If

this is true (I did not see any samples), then S. fragilis (or, more likely, its hybrids) apparently had been

brought to the Northern Caucasus and Siberia with migrations of the

Russian and Ukranian population from the west and northwest rather than

directly from Asia Minor.

Conclusions

Thus from northern and northwestern Asia Minor, where it had a small

primary range in the mountains, brittle willow was somehow introduced to

Europe, where it advanced primarily by means of vegetative reproduction

and formed an enormous secondary range. The plant has been nearly

completely naturalized in the central part of this range; its

alien nature is more obvious in the peripheral

parts. Across all of its secondary range, S. fragilis hybridizes with S. alba on a large scale; in significant parts of the range,

particularly peripheral, non-hybrid specimens are completely

absent.

When and where exactly in Europe did S. fragilis first appear? Is it still continuing to advance? One

might assume that it appeared first within the center of its present

range. However, the actual events could as well be quite different: it is

also possible that the formation of the present locus has been influenced

by climatic factors rather than historic. S. fragilis could have entered Europe somewhere at a peripheral

part of its modern range, such as Italy or the Balkans. In any case,

S. fragilis was likely to be promptly

transported over a great distance. As for its arrival on the Russian

territory, it is clear enough that it came from the west rather than

across the Caucasus.

Quite a number of S. fragilis

herbarium samples have been preserved for 100-150 years. They provide

evidence for the conclusion that during the recent 100-150 years there has

been no significant dynamics in the distribution of this species. For

example, non-hybrid staminate and hybrid pistillate specimens were

collected around Moscow, respectively, in 1837 and 1823; around St.

Petersburg, respectively, in 1850 and 1827; non-hybrid specimens of both

sexes were already present around Mogilev in 1862, and so on. Apparently

the process of colonization in Europe has essentially been completed, so

that S. fragilis has attained its

climatically determined limits. Certainly this is as well indicated by the

concentric zoning pattern described above. Had the process of colonization

been continuing actively into the present time, such a structure could not

yet have been established. Non-hybrid plants definitely have a greater

capacity for self-dispersal than hybrids. Hybrids continue to expand their

range only through new plantings. From the economic standpoint, hybrids

are more valuable, as they grow better. Additionally, hybrids might be

more tolerant to climatic conditions of Mediterranean Region as well as

those in Siberia, since one of the parental species, S. alba, grows naturally in both these regions.

The similarity of the secondary range of S. fragilis and natural ranges of a few European species (Fig. 2)

also signifies that climatic limits might have been already

reached.

Fig. 2. Areas of some European species that resemble

S. fragilis area (adapted

from Meusel et al. 1965)

1. Carex brizoides Juslen. 2. Carex montana L. 3. Anemone nemorosa L.

From the time of the Turkish conquest of the eastern Byzantine

provinces in the 11-12th centuries and to the mid-19th century there was

literally no connection between Europe and eastern Asia Minor. Hence it is

safe to speculate that S. fragilis was

introduced to Europe during the Byzantine Empire rule or maybe even during

the Roman epoch. In one of local British "floras" (Grose 1957: 508), I

came across some curious evidence. In ancient Saxon land deeds of

Wiltshire County (there are fifteen of them, the oldest dated 796), some

willows ("withies") are mentioned as markers of property boundaries.

S. fragilis presently grows at nearly

all of the named locations. Boundary markers were of course preserved and

restored; therefore, it is not improbable that the willows growing there

today are direct descendants of trees that were planted more than a

thousand years ago.

Classic examples of ginkgo, metasequoia, and franklinia show that a

plant with an extremely narrow relict range can be very viable, highly adaptable,

and tolerant to a wide range of conditions. Hence a narrow primary range

of S. fragilis should not be

considered an obstacle for this willow to attain a wide secondary range.

Besides, the phytoclimate of the forested regions in eastern Asia Minor

has much in common with the climate of central Europe.

Veronica filiformis Sm. provides

another example of a species with the natural range in the Caucasus and

Asia Minor extensively naturalized in Europe. Much has been said about it

(Lenmann 1942; Thaler 1953; KornaÅ, Kuc 1954; Bangerter, Kent 1965;

Jehlik, Slavik 1967). This veronica was first found in the wild in 1893 in

France. It has continued colonizing the European countries since then,

mostly (or perhaps exclusively) vegetatively. Its present range embraces

nearly all of central Europe (Fig. 3). Recently it has been found in

Estonia (Eichwald 1960). Similarly to S. fragilis, it appears to advance to the Russian territory from

the west rather than south, i.e., not directly from the Caucasus.

Fig. 3. Distribution of Veronica filiformis Sm. (generalized)

1. primary range 2. secondary range

There remains a single question concerning S. fragilis that yet awaits an answer. Why do

staminate non-hybrid plants have a wider range than pistillate

non-hybrids? Perhaps those were only staminate plants that were initially

introduced. Pistillate plants then might have appeared only many

generations later, as a result of hybrid segregation. Or else, staminate

specimens might have been more capable of vegetative regeneration. It is

quite possible that the right answer is none of the above. It has yet to

be discovered.

References

Adamoviħ L.

1909. Flora Serbiae austro-orientalis. Salix. Rada

Jugosl. Akad., 177: 194-195.

Andersson N. J.

1867. Monographia Salicum 1. Kongl. Svenska

Vetens.-Akad. Handl. 6(1). Stockholm.

Andersson N. J.

1868. Salix. In A.P. De Candolle (ed.).

Prodromus systematis naturalis regni vegetabilis 16

(2): 190-323. GenÃĻve.

Atlas of the British Flora. F.H. Perring, S.M. Walters (eds.).

1962. LondonâEdinburgh.

Aun K.

1939. Eesti pajud. Tallinn.

Bakunin A.A.

1879. Spisok tsvetkovykh rasteniy Tverskoi flory [Flowering

Plants of the Tver Flora. A Checklist]. Tr. SPb obshch.

yestestvoisp. 10.

Bangerter E.B., Kent H.D.

1965. Additional notes on Veronica filiformis. Proc. Bot. Soc. Brit. Isles

6.

Beck v. Mannagetta G.

1909. Flora von Bosnien ... Salicaceae. Wiss. Mitt.

aus Bosnien und Hercegovina 9: 114-119. Wien.

Bertoloni A.

1854. Flora italica 10.

Bononiae.

Bertsch K.

1951. Jahresh. Vereins VaterlÃĪnd. Naturk.

WÞrttemberg 106: 46 (fide LawalrÃĐe 1952: 38; non

vidi).

Boissier E.

1879. Flora Orientalis 4.

GenÃĻveâBasel.

Bonnier G. (s.a.; ca.

1930). Flora complÃĻte illustrÃĐe 10.

Paris.

Borzi A.

1885. Compendio della flora forestale

italiana. Messina.

Bouloumoy L.

1930. Flore du Liban et de la Syrie.

Paris.

Buser R.

1940. Kritische BeitrÃĪge zur Kenntnis der schweizarischen

Weiden. Ber. Schweiz. Bot. Ges. 50:

567-788.

Camus A., Camus E.-G.

1904. Classification des saules d'Europe et

Monographie des saules de France 1. Paris.

Chassagne M.

1956. Inventaire analytique de la flore d'Auvergne et

contrÃĐes limitrophes 1. Paris.

Chernyavskiy P.I., Ploshchakova L. Nedyalkova S., Dimitrov I.

1959. Drveta i khrasti v gorite na Blgariya [BÃĪumer

und StrÃĪucher in der WÃĪldern Bulgariens].

Sofiya

Clapham A.K., Tutin T.G., Warburg E.F.

1962. Flora of the British Isles. 2nd ed.

Cambridge.

Coste H.

1906. Flore descriptive et illustrÃĐe de la

France 3. Paris.

Coutinho A.X.P.

1939. Flora de Portugal. 2nd ed.

LisbÃĩa.

Eichwald K.

1960. Niitjas mailaneâEesti rohumaid ohustav umbrohutaim.

Eesti Loodus 3.

Elwes H.J., Henry A.

1913. Trees and shrubs of Great Britain and

Ireland. 7. Edinburgh.

Em H.

1967. Pregled na dendroflorata na

Macedonija. Skopje.

Fedchenko B.A.

1915. Rastitelnost Turkestana [Vegetation

of Turkestan.] Petrograd.

Fiori A.

1923. Nuova flora analitica d'Italia 1.

Firenze.

Flerov A.F.

1902. Flora Vladimirskoy gub. [Flora of

Vladimir Government]. Moscow.

Flerov A.F.

1912. Flora Kaluzhskoy gub. [Flora of

Kaluga Government] Kaluga.

Fries E.M.

1828. Novitiae florae Suecicae. 2nd ed.

Lund.

GÃķrz R.

1922. Ãber norddeutsche Weiden. Feddes

Repert. 13.

GÃķrz R.

1929. Les saules de Catalogne.

Cavanillesiae 2, 7-10. Barcelona.

GÃķrz R,

1930. BeitrÃĪge zur flora Kleinasiens. Salix. Feddes

Repert. 28.

Goiran A.

1898. Juglandaceae et

Salicaceae veronenses. Bull. Soc. bot.

Ital. 18-24.

Grose J.D.

1957. Flora of Wiltshire.

Devizes.

Grossheim A.A.

1945. Flora Kavkaza [Flora of the Caucasus]

3. 2nd ed. Baku.

Hartig T.

1851. VollstÃĪndige Naturgeschichte der forstlichen

Kulturpflanzen Deutschlands. Berlin.

Hess H.E., Landolt E., Hirzel R.

1967. Flora des Schweiz. 1.

BaselâStuttgart.

Hirc D.

1904. Revizija Hrvatske flore. Salix. Rada Jugoslav.

Acad. 159: 157-162.

Hjelt H.

1902. Conspectus florae fennicae. 2(1).

Helsingforsiae.

Hoffmann G.F.

1791. Historia Salicum iconibus illustrata

2, fasc. 1. Lipsiae.

Host N.T.

1828. Salix.

Vindobonae.

HultÃĐn E.

1950. Atlas Ãķver vÃĪxternas utbredning i

Norden. Stockholm.

Hylander N.

1966. Nordisk KÃĪrlvÃĪxtflora 2.

Stockholm.

Jehlik, N., Slavik B.

1967. DoplÅky k rozÅĄireni Veronica filiformis v Äeskoslovensku.

Preslia 39.

JovanoviÄ? B

1955. Sumske fitocenoze i stamista Suve Planine.

Glasnik sumarskog fakult. 9.

Beograd.

Kerner A.

1860. NiederÃķsterreichische Weiden. Verhandl.

zool.-bot. Ges. Wien 10.

Koch K.

1872. Dendrologie 2 (1).

Erlangen.

Koch W.D.J.

1907. Synopsis der Deutschen und Schweizer

Flora 3. Aufl. Hersg. E. Hallier u. A. Brand.

Leipzig.

KornaÅ J., Kuc M.

1954. Veronica filiformis

Sm. â nowy we flore polskiej uciaÅžliwy chwast lakowy.

Fragm. flor. et geobot. 1(1).

Laguna M.

1883. Flora forestal EspaÃąola 1. Madrid

(n.v.)

LawalrÃĐe A.

1952. Salix. In

Flora gÃĐnÃĐrale de Belgique 1(1).

Bruxelles.

Lehmann E.

1942. Die EinbÞrgerung von Veronica filiformis in Westeuropa.

Gartenbauwissenschaft 16.

Lid J.

1963. Norsk og Swensk flora.

Oslo.

Linton E.F.

1913. The British willows. Suppl. to

J. Bot. 51.

Lojacono M.

1904. Flora Sicula 2(2).

Palermo.

Loudon J.C.

1838. Arboretum et frutecetum Britannicum

3. London.

Lvov P.L.

1956. Opredelitel glavneyshikh derevyev i kustarnikov

Dagestana [Guide to Most Important Trees and Shrubs of

Dagestan.] Makhachkala.

Makhatadze L.B.

1961. Salix. In

Dendroflora Kavkaza [Dendroflora of the Caucasus]

2. Tbilisi.

Marchesetti C.

1897. Flora di Trieste.

Trieste.

Mayevskiy P.F.

1892. Flora Sredney Rossii [Flora of

Central Russia], 1st ed. Moscow;

Mayevskiy P.F.

1895. Flora Sredney Rossii [Flora of

Central Russia], 2nd ed., S.I. Korzhinskiy ed. Moscow.

Mayevskiy P.F.

1902. Flora Sredney Rossii [Flora of

Central Russia], 3rd ed., B.A. Fedchenko ed. Moscow.

Mayevskiy P.F.

1912. Flora Sredney Rossii [Flora of

Central Russia], 4th ed., D.I. Litvinov ed. Moscow.

Medvedev Ya.S.

1883. Derevya i kustarniki Kavkaza [Trees

and Shrubs of the Caucasus]. Tiflis.

Meinshausen K.F.

1878. Flora Ingrica. St.

Petersburg.

Merino B.

1906. Flora descriptiva e ilustrada de

Galicia 2. Santiago.

Meusel H., JÃĪger E., Weinert E.

1965. Vergleichende Chorologie der zentraleuropÃĪischen

Flora 1. Jena

Moss C. E.

1914. The Cambridge British Flora 2.

Cambridge.

NÃĄbÃĐlek F.

1929. Iter turcico-persicum 4. Spisy prirodoved. fak.

univ. Brno 105.

Nazarov [Nasarov, Nasaroff] M.I.

1936. Salix. In

Flora SSSR [Flora of the USSR] 5.

MoscowâLeningrad.

Nazarov [Nasarov, Nasaroff] M.I.

1949. Salix. In

Flora Belorussii [Flora of Byelorussia] 2.

Minsk.

Negodi G.

1944. Flora delle provincia di Modena e Reggio Emilia.

Atti Soc. Natur. Moden. 75.

Nevskiy M.L.

1952. Flora Kalininskoy oblasti [Flora of

Kalinin Oblast] 2. Kalinin.

Parlatore F.

1867. Flora Italiana 4.

Firenze.

Parsa A.

1950. Flore de l'Iran 4.

Teheran.

Penkovskiy V.M.

1901. Derevya i kustarniki, kak dikorastushchiye, tak

i razvodimyye [Wild and Cultivated Trees and Shrubs.]

Kherson.

Petunnikov A.N.

1901. Salix. In [Critical Review of Moscow Flora. III.]

Tr. SPb obshch. yestestvoisp. 31(3):

18-40.

Post G.E.

1933. Flora of Syria, Palestina, and Sinai

2. 2nd ed. Beirut.

Praeger R.L.

1934. The botanist in Ireland.

Dublin.

Pravdin L.F.

1951. [Willow.] In Derevya i kustarniki

SSSR [Trees and Shrubs of the USSR] 2.

MoscowâLeningrad.

Protopopov G.F.

1953. Salix. In

Flora Kirgizskoy SSR [Flora of Kirghiz SSR] 4:

9-37. Frunze.

Rechinger K.H.

1957. Salix. In Hegi G.

Illustrierte Flora von Mitteleuropa 3(1): 44-135.

Aufl. 2. MÞnchen.

Rohlena J.

1942. Conspectus florae Montenegrinae.

Preslia 20-21.

Rouy G.

1910. Salix. In

Flore de France 12: 189-252. Paris.

Rozeira A.

1944. A flora da provincia de Tras-os-Montes. Memor.

Soc. Broter. 3.

Rozen V.V.

1916. [Checklist of Plants Found in Tula Government up until

1916.] Izv. Tulsk. obshch. lyubit. yestestvozn.

4.

Sarfatti G.

1959. Prodromo della flora della Sila.

Webbia 15.

Schrank F.P.

1789. Baierische Flora 1.

MÞnchen.

Seemen O., v.

1908-1910. Salix. In Ascherson

P., Graebner P. Synopsis der mitteleuropÃĪischen

Flora 4: 54-350. Leipzig.

Siuzev P.V.

1901. [On some new plants of Moscow flora.] Tr. bot.

sada Yuryev. un-ta 2(1).

Skvortsov A.K.

1956. [Some additions and amendments to the willow flora of West

Siberia.] Sistem. zametki gerbariya Tomsk. un-ta

79-80: 13-15.

Skvortsov A.K.

1966. [Review of willows from the Caucasus and Asia Minor.]

Tr. Bot. in-ta AN ArmSSR 15: 91-141.

Skvortsov A.K.

1968. Ivy SSSR [Willows of the USSR.]

MoscowâLeningrad.

SoÅĄka T.

1938-1939. BeitrÃĪge zur Kenntnis der Schluchtenfloren von SÞdserbien

1-7. Glasnik Skopskog nauchnog drushtva 18,

20.

Å panoviÄ? T.

1954. Vrbe naÅĄih podunavskih ritova.

Å umarski List 78: 506-521.

Zagreb.

Stefanov B.

1943. Fitogeografski elementi v Blgaria. Sb. Blg.

Akad. 39. Sofia.

Syreishchikov D.P.

1907. Illustrirovannaya flora Moskovskoy

gub. [Illustrated Flora of Moscow Government] 2.

Moscow.

Syreishchikov D.P.

1927. Opredelitel rasteniy Moskovskoy gub.

[Guide to the Plants of Moscow Government.] Moscow.

Szafer W.

1921. Salicaceae. In Flora

Polska 2: 24-47. KrakÃģw

Thaler I.

1953. Die Ausbreitung von Veronica filiformis. Phyton 5.

Toeppfer A.

1914. Salicaceae. In Vollmann F.

Flora von Bayern: 187-202.

Stuttgart.

Tsinger V. Ya.

1886. Sbornik svedeniy o flore Srednei

Rossii [Anthology of Knowledge about the Flora of Central

Russia.] Moscow.

Vicioso C.

1951. Salicaceas de EspaÃąa.

Madrid.

White F.B.

1890. A revision of the British willows. J. Linn.

Soc. 27.

Wimmer F.

1866. Salices Europaeae.

Vratislaviae.

WoÅoszczak E.

1889. Kritische Bemerkungen Þber siebenbÞrgische Weiden.

Ãsterreich. bot. Z. 62: 291-295;

330-332.

Zangheri P.

1966. Flora e vegetazione del medio ed alto Appenino Romagnolo.

Webbia 21.

Zodda G.

1954. La flora teramana. Webbia

10.

NOTES

Translation I.Kadis

1 Jan 2008